For Ernie Kovacs, that is: Mother spent some time in Mr. Benchley's villa this morning searching for a lost bottle of Drambuie (she just loves that crown cork), and while she was there Wiki (and alcohol) told her: Ernie Kovacs (b. Ernest Edward Kovacs, January 23, 1919, Trenton, New Jersey; d. January 13, 1962, Los Angeles, California), was an American comedian whose uninhibited, often ad-libbed, and visually experimental comic style came to influence numerous television comedy programs for years after his tragic, early death in an automobile accident. Such later, iconoclastic shows as Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In, Monty Python's Flying Circus, The Uncle Floyd Show, and Saturday Night Live and TV hosts like David Letterman are seen as bearing Kovacs's influence.

At at NBC's Philadelphia affiliate, WPTZ, Kovacs first began to use the ad-libbed and experimental style that would come to make his reputation, including video effects, superimpositions, reverse polarities and scanning, and quick blackouts. He was also noted for abstraction and carefully-timed non-sequitur and for carefully allowing the so-called "fourth wall" to be breached by having cameras show his viewers activity past the show set---including crew members and, on occasion, outside the studio itself. Kovacs also liked talking to the off-camera crew and even introduced segments from the studio control room.

Kovacs helped develop camera tricks still common almost fifty years after his death, one of which became one of his signature gags: his character, Eugene, sitting at a table to eat his lunch, removing items one at a time from a lunch box, and letting them roll down the table "mysteriously" to a man reading a newspaper at the other end, while Kovacs poured milk from a thermos bottle in a seemingly unusual direction. Never seen on television before Kovacs tried it, the gag's secret was using a tilted table in front of a camera tilted to the same angle.

Kovacs constantly sought new techniques and used both primitive and improvised ways of creating visual effects that would be done electronically after his time. One such innovative gag involved attaching a kaleidoscope to a camera lens with cardboard and tape, and setting the resulting abstract images to music. Another involved Kovacs---an inveterate cigar smoker---sitting in an easy chair, reading his newspaper, smoking his cigar, and removing it from his mouth to exhale white smoke. The trick: He was made to seem underwater, with the smoke turning out to be a small amount of milk with which he filled his mouth before "submerging."

He also developed such routines as an all-gorilla version of Swan Lake; a poker game set to Beethoven's Fifth Symphony; The Nairobi Trio, three derby-hatted apes miming mechanically to the tune "Solfeggio"; the Silent Show, in which a nerdy character interacts with the world accompanied solely by music and sound effects; parodies of typical television commercials and movie genres; and various musical segments with everyday items (such as kitchen appliances or office equipment) moving in sync to music.

Kovacs could use extended sketches and mood pieces or quick blackout gags lasting only seconds. Some of these could be expensive, such as his famous used car salesman routine with a jalopy and a breakaway floor---it cost a reported $50,000 to produce the six-second gag. He was also one of the first television comedians to use odd fake credits and comments between the legitimate credits and, at times, during his routines.

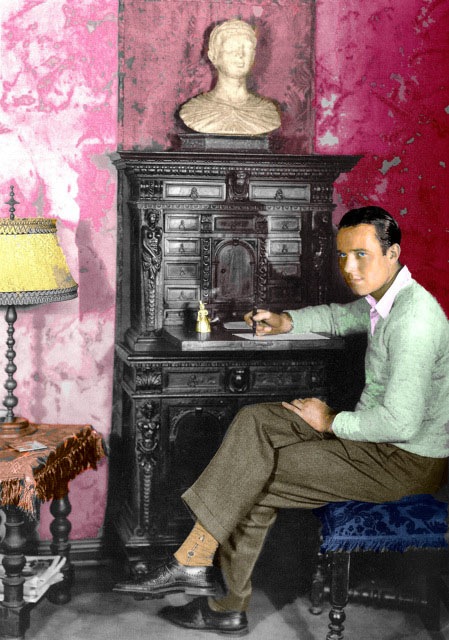

His most familiar characters included fey, lisping poet Percy Dovetonsils; German disc jockey Wolfgang von Sauerbraten; horror show host Auntie Gruesome; bumbling magician Matzoh Heppelwhite; Miklos Molnar, the sardonic Hungarian host of a cooking show; Frenchman Pierre Ragout; the silent character Eugene (above); and Mr. Question Man, who would answer queries supposedly sent in by viewers.

Kovacs's television programs included Three to Get Ready; Time for Ernie (1951); Ernie in Kovacsland (also 1951); The Ernie Kovacs Show (1952-1953; 1955-1956); a twice-a-week job filling in for Steve Allen as host of The Tonight Show (1956-57); and, a game show, Take a Good Look (1959-1961).

He also did several television specials, including the famous Silent Show (1959)---featuring his character, Eugene, the first all-pantomime prime-time network program---and a series of monthly half-hour specials for ABC in 1961-62. The latter---shot on videotape, using new editing and special effects techniques---are often considered his best television work; he won an Emmy Award for the 1961 series.

But what made Kovacs unique may also have been what made him a hard sell to television viewers used to situation comedies and variety shows. Considered ahead of his time, and having a cult following at best, Kovacs rarely had a highly-rated show. His friend Jack Lemmon was once quoted as saying no one ever understood Kovacs's work because "he was always 15 years ahead of everyone else.

Kovacs married his first wife, Bette Wilcox, on August 13, 1945. When the marriage ended, he fought for custody of their children, Elizabeth 'Bette' and Kip Raleigh 'Kippie'. The courts awarded Kovacs full custody upon determining that his former wife was mentally unstable. This decision was extremely unusual at the time, setting a legal precedent. Wilcox subsequently kidnapped the children, taking them to Florida. After a long and expensive search, Kovacs regained custody."

Kovacs married actress and singer Edie Adams on September 12, 1954 in Mexico City. The ceremony was presided over by former New York City mayor William O'Dwyer, and performed in Spanish, which neither Kovacs nor Adams understood; O'Dwyer had to prompt each to say "Si" at the "I do" portion of the vows. Adams, who had a very white-bread middle-class upbringing in suburban New Jersey, was smitten by Kovacs's quirky way; the couple remained together until his death. (Adams later said about Kovacs, "He treated me like a little girl, and I loved it -- Women's Lib be damned!").

The couple had one daughter, Mia Susan Kovacs born June 20, 1959; Adams also supported Kovacs's struggle to reclaim his two older children after their kidnapping by their mother. But she also became a frequent partner on his television shows, including participating in Nairobi Trio routines. Kovacs usually introduced or addressed her in a businesslike way, as "Edith Adams"; Adams was usually willing to do anything he envisioned, whether singing seriously, performing impersonations (including a well-regarded impression of Marilyn Monroe), or taking a pie in the face or a pratfall if and when needed.

Kovacs found modest success as a character actor in Hollywood movies in his final years, often typecast as a swarthy military officer in such films as Operation Mad Ball and Our Man in Havana. But he also garnered critical acclaim for roles such as the perennially inebriated writer in Bell, Book and Candle and as the cartoonishly evil head of a railroad company (who resembled Orson Welles' title character in Citizen Kane) in It Happened to Jane. His own personal favorite was said to have been the offbeat Five Golden Hours (1961), in which he portrayed a larcenous professional mourner who meets his match in professional widow Cyd Charisse.

Shortly before his death, Kovacs had been chosen to appear as Melville Crump in Stanley Kramer's star-packed comedy It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, with Adams portraying his screen wife Monica Crump. The role eventually went to comedian Sid Caesar.

Ten days before his 43rd birthday, Kovacs was killed in an automobile accident in Los Angeles. After meeting Adams at a party hosted by Milton Berle and his wife, the couple left in separate cars---Kovacs had been working for much of the evening before the party---and, during an unusual southern California rainstorm, the comedian lost control of the Chevrolet Corvair station wagon while turning fast, crashing into a power pole at the corner of Beverly Glen and Santa Monica Boulevards, and being thrown halfway out the passenger side, dying almost instantly from chest and head injuries.

Rumors suggested Kovacs lost control of the car while trying to light a cigar. A photographer managed to arrive moments later, and morbid images of Kovacs in death appeared in newspapers across the United States. Years later, in a documentary about Kovacs, Edie Adams revealed she telephoned the coroner's office impatiently when she learned of the crash, and an official cupped the telephone, saying to a colleague it was "Mrs. Kovacs" and what should he tell her; she became inconsolable upon the confirmation. Jack Lemmon, who also attended the Berle party, identified Kovacs's body at the morgue when Adams became too overcome to do it.

A frequent critic of the U.S. tax system, Kovacs owed the IRS several hundred thousand dollars in back taxes thanks to his simple refusal to pay the brunt of them; up to 90% of his earnings would be garnished as a result. Adams (who married and divorced twice after Kovacs's death) paid the debt off herself, refusing help from celebrity friends (who planned a benefit concert for the purpose), though she did accept film and television work from them, instead.

Kovacs is buried in Forest Lawn - Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles. His epitaph reads: "Nothing in moderation-We all loved him". Only one of Kovacs's three children survives, his oldest, Elisabeth (from his first marriage); Kippie, his second, died at age 52 after a long illness and a lifetime of poor health July 28, 2001. His only child with Edie Adams, Mia Susan, was killed May 8, 1982---also in an automobile accident; Mia and Kippe are buried close to their father. Keigh Lancaster, Kovacs's only grandchild, was born to Kippie and her husband, screenwriter Bill Lancaster (the son of actor Burt Lancaster).

Sunday, January 6, 2008

It all turned to shit Forty-six years ago today

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

_02.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment